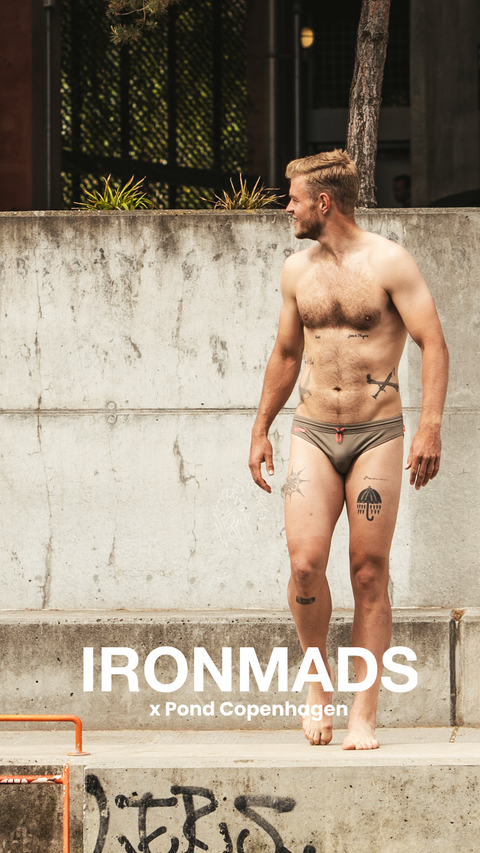

Swimmers, trunks, speedos, budgie smugglers - call ‘em what you will, brief swimwear has been making a splash (literally and figuratively) over the past couple of years, with more than one magazine or newspaper headline heralding their return to beaches and swimming pools across the world. But it’s not the first time such a small piece of nylon fabric has caused such a furore…

The invention of the speedo style of swimwear is generally credited to an ex-pat Scotsman, Alexander McRae, who moved to Australia and set up a hosiery and beachwear company in the early twentieth century. Ever an innovator, he championed the use of cotton and silk instead of wool for his first (rather more modest) one-piece swimming costumes that had cut-away racer backs instead of sleeves.

"Board shorts: the swimsuit that ensures the male figure is cut off from navel to knee; the article of clothing that makes you wonder if you’re actually swimming in a skirt; those 25 yards of fabric that never actually seem to dry..."

John Gerry, Medium.com

As these proved so popular with sports swimmers due to their much-reduced drag in the water, McRae went one step further and provided the 1936 men's Olympic team with shorts - the first time professional swimmers had gone bare-chested.

Highs and Lows

As the century progressed, swimming briefs became…well… briefer, as both professional swimmers and casual dippers realised the comfort of wearing next to nothing. Initially shocking - a bunch of speedo-wearing guys were arrested on Bondi Beach in 1961 for ‘indecent exposure’ - the popularity of skimpy nylon swimwear rose as the sexual revolution swept across the Western world.

"I was Moses cutting through the Red Sea — fast, smooth, and free gliding from board-short captivity to bikini-bottom independence. There was no extra fabric dragging me down to my death; no drawstring coming undone to showcase my cold water shrinkage; no air bubbles getting caught in my pockets like tiny baby farts."

John Gerry, Medium.com

Men wanted to look sexy, and a well-fitted pair of trunks allowed maximum skin, chest hair (and probably medallion) exposure. The 70s and early 80s saw the zenith of the speedo with Olympic swimmer Mark Spitz famously photographed in nothing but a stars and stripes pair and his seven gold medals in 1972. And Tom Selleck showed he was all man as he ran through the surf in Malibu in his rather fetching navy blue version.

The Long and Short of It

Sadly, by the 1990s, jock culture had become prevalent on the beach, and loose board shorts were the norm, forcing a generation of poor swimmers to face the discomfort, chafing and interminable dampness of baggy fabric shorts. Unflattering and impractical, these shorts were often in garish colours or ugly prints, but they suited the macho vibes of the late twentieth century.

However, as the years ticked on, the prevailing dominance of American culture seemed to lose a bit of its appeal. Maybe an orange buffoon as president finally put the nail in the coffin of US dominance, but recent years have seen a strong surge back to the liberating - and more European - swim brief.

"The global attitude about speedos for men is becoming increasingly tolerant, deemed acceptable by more than 70 percent of respondents, an eight percent increase over last year."

Expedia Flip-Flop Report 2017

Inspired perhaps by a certain Mr Gandy in an aftershave advertisement or Daniel Craig as Bond, striding out from the sea in skin-tight trunks, a whole new generation discovered that speedos beat baggies hands down, both in comfort and in style. Athletic guys now know that nothing highlights abs and ass better than a well-cut brief swimsuit, whilst bigger gentlemen realised that baggy shorts formed a very unflattering rectangle below the belly that actually made them look even larger.

GQ Magazine UK

Finally, people can see again that if you get the fit right, EVERYONE looks good in a speedo. Briefer IS better after all.

DID YOU READ: How many speedos does a true water lover really need?

This read was written by contributing writer and fashion editor Graham Addinall.